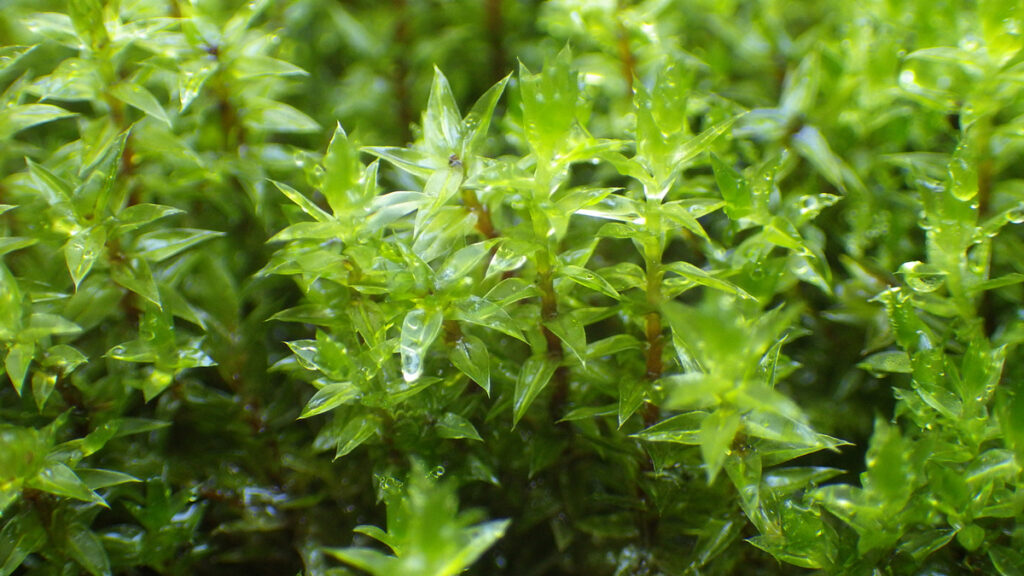

Mosses (Bryophyta), small plant organisms that never grow independently but in dense clumps in moist habitats (both terrestrial and freshwater), have a very simple structure with a small stem and leaves. However, in case of mosses, these structural elements cannot be attributed to the standard stem and leaf that we see in other plants, and they do not even have a root, but develop rhizoids, filamentous formations with which they attach to the substrate. Also, you will never see a moss flower, but both male and female reproductive organs will develop at the top of its stem, or they will be developed each on a separate plant. Today, around 13,000 species of mosses are known in the world, and their unique evolutionary history spans almost 400 million years. As many as 58 new species of mosses have been found in Croatia in the last 10 years.

The importance of mosses in freshwater systems such as the Plitvice Lakes and especially in the development of tufa barriers is fascinating. These small plants that grow densely covering certain parts of tufa barriers and cascades, participate as a biological factor in the process of tufa creation; however, but this does not apply to all species of moss, but only to some.

The process of tufa formation, the growth of tufa barriers and ultimately the damming of the lake is a very specific process that involves both chemistry and biology, and one would not be possible without the other.

Mosses play a significant role in the tufa creation process. Mosses, like other plant organisms, create oxygen in the process of photosynthesis. However, terrestrial plants use carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air for this process, while freshwater mosses cannot use carbon dioxide from the air, but use it from dissolved hydrogen carbonate (HCO3–) for photosynthesis. The waters of the Plitvice Lakes are rich in this compound, and at the moment when carbon dioxide is used up for photosynthesis, calcium carbonate crystals (CaCO3) are isolated and tufa is formed! Under favourable conditions, tufa will settle on the moss stem, almost “burying” it, while the moss will continue to grow and look for ways to get water and light. The lower parts will thus remain covered in tufa, and the upper parts without tufa will continue to grow. The lower parts will eventually form tufa with some other plant and animal remains.

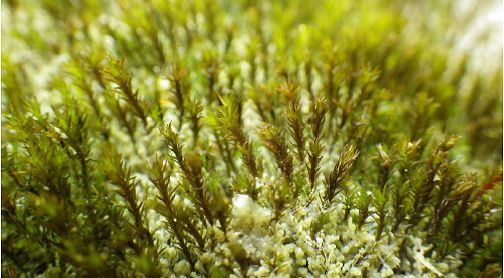

Previous research on mosses in the Plitvice Lakes identified 34 species of mosses, but a more recent research conducted from 2016 to 2019 recorded as many as 44 species of mosses on tufa barriers and surrounding cascades. Mosses in places of fast water flow and stronger mechanical action of the water grow, however, with a smaller number of species, which in turn increases towards the peripheral parts of the cascade.

The most common species of moss in the Plitvice Lakes is Palustriella commutata, which participates in the sedimentation of tufa, as well as other species such as Eucladium verticillatum and Ptychostomum pseudotriquetrum as well as Hymenostylium recurvirostrum, which is more common in the Lower lakes.

The species Didymodon tophaceus can also be found in the Lower lakes, which in previous research was recorded as a significantly more abundant species in several localities, while recent data indicate its rarity and growth only in the most open and unshaded localities, such as the Milka Trnina waterfalls and the Great Waterfall.

The value of freshwater mosses for Plitvice Lakes is unquestionable. Their participation in the tufa creation process and the development of fascinating tufa barriers and significant biological diversity contribute to the appearance of the Plitvice Lakes, which we admire and which we want to preserve.

Read other interesting stories from the Plitvice Lakes National Park